10 Criterion Validity Examples

Dave Cornell (PhD)

Dr. Cornell has worked in education for more than 20 years. His work has involved designing teacher certification for Trinity College in London and in-service training for state governments in the United States. He has trained kindergarten teachers in 8 countries and helped businessmen and women open baby centers and kindergartens in 3 countries.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Chris Drew (PhD)

This article was peer-reviewed and edited by Chris Drew (PhD). The review process on Helpful Professor involves having a PhD level expert fact check, edit, and contribute to articles. Reviewers ensure all content reflects expert academic consensus and is backed up with reference to academic studies. Dr. Drew has published over 20 academic articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education and holds a PhD in Education from ACU.

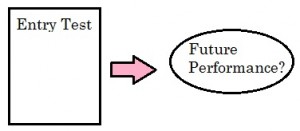

Criterion validity is a type of validity that examines whether scores on one test are predictive of performance on another.

For example, if employees take an IQ text, the boss would like to know if this test predicts actual job performance.

- If an IQ test does predict job performance, then it has criterion validity.

- If an IQ test does not predict job performance, then it does not have criterion validity.

To make that determination, a correlation is calculated between the IQ scores and a measure of job performance.

The higher the value of the correlation, the stronger the relation between the two and the higher the criterion validity.

Sometimes this is also called predictive validity .

Of course, there are other factors related to job performance, so the correlation will never be perfect (i.e., 1). In most situations, there will be many factors associated with a particular performance outcome, and in some cases, hundreds.

Examples of Criterion Validity

1. leadership inventories and leadership skills.

A leadership inventory can predict whether someone will be good in a leadership role.

Predictor Variable : High score on a leadership inventory Criterion Variable: Aptitude for a leadership role

It takes a long time to know which employees have leadership potential. They have to be seen in various situations over a period of years to develop a solid understanding of their personality and ability to handle pressure.

That is very inefficient, especially for a new company that is expanding rapidly.

This is where personality inventories come into play. By administering a test that assesses leadership traits, a company can obtain a lot of data about a large number of employees very rapidly.

The key issue is: make sure a test with criterion validity is administered. As long as the test has criterion validity, it will be able to predict, with some degree of accuracy , which employees are suitable for a leadership role.

Here is a list of commonly used leadership inventories.

2. The SAT and College GPA

Studies have found that SATs have a weak to moderate ability to predict your college GPA.

Predictor Variable: SAT Score Criterion Variable: College GPA

There have been many studies on the criterion validity of SAT scores in predicting college GPAs (Kobrin et al., 2008).

The basic premise is that the SAT has criterion validity regarding college performance. The typical studying involves obtaining the SAT scores of hundreds, even thousands of students, and then correlating those scores with first year or final year GPAs.

Although it is difficult to make a sweeping statement that adequately covers so many studies, the results range from finding weak to moderately strong associations between SAT and GPA.

A moderately strong association is more impressive than what it sounds. It’s just one score on one test, but it predicts future performance on a criterion fairly well. If researchers were to include other factors, such as motivation and time-management skills, the ability to predict a student’s college GPA would become increasingly more accurate.

3. The Housing Market

Predictor variables, including number of new homes purchased, building permits awarded, interest rates on mortgages, and employment rate have high criterion validity in predicting the prices of houses .

Predictor Variables: Building permits issued, interest rates on mortgages, employment rate Criterion Variable: Housing prices

The housing market is a classic indicator of economic performance. The volume of sales each quarter are affected by numerous factors, including: the employment rate, interest rates, building supply, and consumer confidence, just to name a few.

Each one of those factors can be measured and correlated with the housing market. Some factors have strong criterion validity, while others may have moderate or low criterion validity. However, when economists put them all together, the ability to predict the housing market improves significantly.

Of course, it’s still not an exact science, so there will always be some margin of error in those forecasts.

4. Psychological Correlates of Academic Performance

Self-efficacy and effort management are found to have high criterion validity in academic performance tests because they are predictors of a high GPA.

Predictor Variable: Self-efficacy and effort management Criterion Variable: A high GPA

Richardson et al. (2012) examined a large number of studies between 1997 and 2010 that involved identifying psychological variables associated with academic performance. The researchers included over 7,000 studies and identified over 80 distinct variables that correlated with GPA.

Each of those 80 variables have a degree of criterion validity. That is, a student’s score on each one of those variables is predictive of grades to some extent. The real question is: which ones are the best predictors?

After conducting some very thorough analyses, the results indicated that psychological factors such as self-efficacy and effort management were the strongest correlates of GPA. In other words, student self-efficacy and effort management have criterion validity regarding GPA.

5. The In-Basket Activity

The in-basket job simulation test examines a manager’s ability to prioritize tasks. It gets a job applicant to sort items in an in-basket and sort the order in which to do them.

Predictor Variable: Performance in the in-basket exercise Criterion Variable: Applicant’s aptitude as a manager

The In-Basket activity is a job simulation task that is designed to assess an applicant’s ability to prioritize.

First, the applicant is seated at an official-looking desk and instructed to sort through the in-basket documents. The basket contains memos, email printouts, messages, and descriptions of various tasks that the company needs completed.

The applicant is given a short period of time to read the assorted documents and arrange them in order of priority.

This is an example of the type of assessment tool that an HR department will implement because they believe it has criterion validity. Performance in this activity is predictive of the ability to prioritize competing demands on the job.

6. Criterion Validity and Life-Expectancy

A life-expectancy test will have criterion validity if it can reliably predict the correlation between a predictor variable such as frequent exercise and longevity of life.

Predictor Variable: Regular exercise Criterion Variable: A long life.

It seems like every month another study on life-expectancy is published.

Many of the studies have similar methodologies; at stage 1, thousands of people are assessed on a multitude of factors, including dietary habits, frequency of exercise, and psychological factors such as social support and personality characteristics.

At stage 2, approximately 20-50 years later, the researchers gather data on physical health such as cardiovascular disease and cancer.

By examining the correlations between the factors assessed at stage 1 with the health status of participants at stage 2, the researchers can determine which factors have criterion validity. That is, which factors at stage 1 are related to health at stage 2.

7. The NFL Combine

The NFL Combine is an annual test of college football platers’ aptitude to play in the NFL. Most of these tests don’t have criterion validity, but the sprint test for running backs does predict future performance in the NHL.

Predictor Variable: NFL combine sprint test Criterion Variable: Running back performance in the NFL

Every year, top college football players are invited to participate in the NFL’s combine. The event lasts several days and involves each athlete going through a wide range of physical challenges, such as running the 40-yard dash, jumping as high as they can, and taking an interesting IQ test called the Wonderlic.

Head coaches, scouts, and owners put a lot of faith in the results of these tests, but no one is really sure why. As research by Kuzmits & Adams (2008) has revealed, there is “…no consistent statistical relationship between combine tests and professional football performance, with the notable exception of sprint tests for running backs” (p. 1721). For a non-technical explanation, click here .

The NFL combine may be one of the most enduring set of tests that completely lack criterion validity.

8. Bus Driver Course Performance and Bus Accidents

To test the criterion validity of a driver course, researchers would have to follow-up on large experimental and control groups to see whether those who took the driver course were in less accidents.

Predictor Variable: Taking a bus driver safety course Criterion Variable: Having less bus accidents on the job

Hiring skilled and cautious bus drivers is a paramount concern for many municipalities. A single accident can result in numerous injuries. Add in the duration of driving times and the number of buses operating at any given time, and the situation is ripe for frequent accidents.

Therefore, bus companies need to select their drivers carefully. One component of the hiring process involves applicants driving through a standardized course. The course has been designed to mimic several characteristics found in real driving conditions and each applicant’s performance can be objectively measured and scored.

When that score is then correlated with actual driving records of hired drivers over the next few years, its criterion validity can be assessed.

Hopefully, the bus company will discover that the driving course has criterion validity. In other words, performance on the course can predict actual job performance. So, applicants that do poorly on the course, should not be hired.

9. Job Simulation and Nursing Competence

Evaluations of competence sometimes have low criterion validity. For example, one study of nursing competence from external experts did not correlate with the evaluations of the day-to-day supervisors of those nurses, suggesting that either the experts or supervisors are conducting assessments with low criterion validity.

Predictor Variable: Assessments of performance by supervisors Criterion Variable: Actual on-the-job performance

Nursing is an incredibly high-pressure, high-stakes occupation. Poor job performance can result in serious injury or worse. Therefore, the ability to develop accurate measures of performance that have criterion validity is of substantial importance.

Unfortunately, relying on a paper and pencil measurement of skills fails to replicate the high-stress situations that nurses often find themselves facing.

However, “Evaluation of clinical performance in authentic settings is possible using realistic simulations that do not place patients at risk” (Hinton, et al., 2017, p. 432).

In the Hinton et al. study, nurses engaged in specific medical-surgical test scenarios with manikins in a high-fidelity laboratory while being observed by experienced professionals. Those ratings were then compared to their supervisor’s ratings on the job.

In this example, the researchers were attempting to establish the criterion validity of the simulation scenarios to predict on-the-job performance. Despite all the effort that went into this study, scores on the simulated scenarios “… were not well correlated with self-assessment and supervisor assessment surveys” (p. 455).

10. Wearable Trackers and Steps Walked

Step counters that you wear on your watch apparently have high criterion validity. To test this, Adamakis (2021) got people to jog on a treadmill, counted their steps, then compared it to the results on the step counter. The step counters did pretty well!

Predictor Variable: Steps recorded on a step counter Criterion Variable: Actual steps walked

Ever wonder if those activity trackers on your phone are accurate? Well, research by Adamakis (2021) may shed some light on this question.

In this study, thirty adults wore two smartphones (one Android and one iOS), while running four apps: Runtastic Pedometer, Accupedo, Pacer, and Argus. They walked and jogged on a treadmill at three different speeds for 5 minutes. Two research assistants counted every step they took with a digital counter.

Criterion validity of the apps was then assessed by comparing the data from the apps with the 100% accurate digital counters. The results revealed that “The primary finding regarding step count was that all freeware accelerometer-based apps were valid…when comparing iOS and Android apps, Android apps performed slightly more accurately than iOS ones” (p. 9).

So, it seems that these apps have acceptable criterion validity, at least when it comes to counting steps.

This study was also a good example of concurrent validity because the validity of one test was established by conducting the test concurrently (e.g. at the same time) as another test known to be valid, to see if they get the same results.

With the prevalence of tests used to determine who gets into college or who gets hired as a bus driver, it would be nice to know if those tests are accurate. That is, is a person’s score on a given test at all related to actual performance, either at school or on the job?

As it turns out, there is a way to make this determination, and it’s called criterion validity. The usual methodology involves administering the test to a group of people and then assessing their performance in a given domain at a later date. That later date could be a matter of months or several years.

Fortunately, researchers have conducted a great deal of studies examining the criterion validity of thousands of various tests. Tests that lack support are usually dropped or modified, while tests that are supported by research can be used in many practical situations.

Adamakis, M. (2021). Criterion validity of iOS and Android applications to measure steps and distance in adults. Technologies, 9 , 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/technologies9030055

Cohen, R. J., & Swerdlik, M. E. (2005). Psychological testing and assessment: An introduction to tests and measurement (6th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Hinton, J., Mays, M., Hagler, D., Randolph, P., Brooks, R., DeFalco, N., Kastenbaum, B., & Miller, K. (2017). Testing nursing competence: Validity and reliability of the nursing performance profile. Journal of Nursing Measurement, 25 (3), 431. https://doi.org/10.1891/1061-3749.25.3.431

Kobrin, J. L., Patterson, B. F., Shaw, E. J., Mattern, K. D., & Barbuti, S. M. (2008). Validity of the SAT for predicting first-year college grade point average (College Board Research Report No. 2008-5). New York, NY: College Board.

Richardson, M., Abraham, C., & Bond, R. (2012). Psychological correlates of university students’ academic performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin , 138 (2), 353.

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ 23 Achieved Status Examples

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ 25 Defense Mechanisms Examples

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ 15 Theory of Planned Behavior Examples

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ 18 Adaptive Behavior Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 23 Achieved Status Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 15 Ableism Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 25 Defense Mechanisms Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 15 Theory of Planned Behavior Examples

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Criterion Validity | Definition, Types & Examples

Introduction

What is criterion validity, why is criterion validity important, types of criterion validity, other types of validity, establishing criterion validity.

Criterion validity is a key concept in research methodology , ensuring that a quantitative test or measurement accurately reflects the intended outcome. This form of validity is essential for evaluating the effectiveness of various assessments and tools across different fields.

By comparing a new measure to outcomes from an established test, researchers can determine how well the new measure predicts or correlates with the criterion outcome. Understanding criterion validity is crucial for designing a new valid measure and conducting robust quantitative research.

This article outlines the definition, types, and examples of criterion validity, providing a clear and concise guide for researchers and students alike.

Criterion validity refers to the extent to which a measurement or test accurately predicts or correlates with an outcome based on an established criterion.

It is a critical aspect of evaluating the effectiveness of a new tool or assessment method. The primary goal of criterion validity is to determine whether the results of a new and validated measure align with the outcomes of previous measures.

There are two main ways to assess criterion validity: concurrent validity and predictive validity. Concurrent validity examines the correlation between the new measure and an established measure taken at the same time. This type of validity is useful when researchers need to validate a new test quickly, using existing, reliable data.

Predictive validity, on the other hand, assesses how well the new measure predicts future outcomes. This approach is particularly valuable in fields like psychology, education, and health, where predicting future performance or behavior is crucial.

For instance, in educational testing, a new reading comprehension test may be evaluated for criterion validity by comparing its results with those of an established test known to be reliable. If the new test's scores closely match the established test's scores, it demonstrates high concurrent validity. Alternatively, if the new test can accurately predict students' future academic performance, it exhibits high predictive validity.

Establishing criterion validity is essential for ensuring that a measurement tool is both accurate and reliable. Without it, the results of a study or assessment may be questionable, leading to incorrect conclusions or ineffective interventions.

Therefore, understanding and applying criterion validity is fundamental in research to develop robust and credible measurement instruments.

Criterion validity is crucial because it ensures the accuracy and reliability of measurement tools used in research. By confirming that a new measure accurately reflects or predicts an established criterion, researchers can trust the results and conclusions drawn from their studies.

One primary reason criterion validity is important is that it helps verify the effectiveness of new assessment tools. For instance, in educational settings, developing a new test for measuring students' mathematical abilities requires validation against a trusted, established test. If the new test demonstrates high criterion validity, educators can confidently use it to assess and improve students' skills.

In clinical psychology, criterion validity is vital for diagnosing and predicting outcomes. A new diagnostic tool for depression, for example, must be validated against existing, reliable diagnostic criteria.

High criterion validity ensures that the new tool accurately identifies individuals with depression and predicts their future mental health outcomes. This validation is essential for providing effective treatment and support.

Criterion validity also plays a significant role in employment and organizational settings. For example, when developing a new job performance assessment, it is important to validate it against current performance measures.

High criterion validity indicates that the new assessment accurately predicts job performance, aiding in effective hiring and employee development decisions.

Moreover, criterion validity contributes to the persuasiveness of research findings. When a measure demonstrates strong criterion validity, researchers can apply the findings across different contexts and populations with greater confidence. This broader applicability enhances the impact and utility of research.

Criterion-related validity is divided into several types, each serving a distinct purpose in evaluating how well a new measure correlates with or predicts an established outcome.

The primary types of criterion validity are concurrent validity, predictive validity, convergent validity, and discriminant validity. Each type provides a different perspective on the effectiveness and reliability of a measurement tool.

Concurrent validity

Concurrent criterion validity assesses the extent to which a new measure correlates with an established measure taken at the same time. This type of validity is particularly useful when researchers need to validate a new tool quickly using existing, reliable data.

By comparing the results of the new measure with those of a well-established criterion measure administered concurrently, researchers can determine if the new measure produces similar outcomes.

For example, in the context of educational testing, if a new reading comprehension test is administered alongside a well-validated reading test, and the scores from both tests show a strong correlation, the new test is said to have high concurrent validity. This indicates that the new test is effective in measuring the same construct as the established test.

Predictive validity

Predictive criterion validity evaluates how well a new measure predicts future outcomes based on an established criterion. This type of validity is essential in fields where forecasting future performance or behavior is critical, such as psychology, education, and healthcare.

By demonstrating predictive validity, researchers can show that their new measure is not only reliable in the present but also useful for making accurate predictions about future events or behaviors.

For instance, a new aptitude test designed to predict students' success in college might be validated by comparing its scores to students' future academic performance. If the test scores accurately predict how well students will perform in their college courses, the test exhibits high predictive validity. This type of validity is crucial for creating tools that aid in long-term planning and decision-making.

Convergent validity

Convergent validity is a subtype of criterion validity that examines whether a measure correlates well with other measures of the same construct. High convergent validity indicates that the new measure is consistent with other established measures that assess the same concept.

This type of validity is essential for ensuring that different tools intended to measure the same construct produce similar results, thereby supporting the robustness and credibility of the new measure.

For example, if a new scale for measuring anxiety levels shows a high correlation with existing, validated anxiety scales, it demonstrates high convergent validity. This consistency across different measures provides confidence that the new scale is accurately assessing anxiety.

Discriminant validity

Discriminant validity, another subtype of criterion validity, evaluates whether a measure does not correlate with measures of different constructs. High discriminant validity ensures that the new measure is distinct and not merely reflecting other unrelated constructs.

This type of validity is important for establishing the uniqueness of a new measure and confirming that it is not inadvertently assessing something else.

For instance, if a new test designed to measure depression shows low correlation with measures of unrelated constructs like intelligence or physical health, it has high discriminant validity. This demonstrates that the new test specifically assesses depression without being confounded by other relevant criterion variables.

Research made simple and easy with ATLAS.ti

Look to our powerful data analysis tools to unlock the insights in your research. Start with a free trial today.

In addition to criterion validity, several other types of validity are essential for evaluating the accuracy and reliability of measurement tools. These include construct validity, face validity, and content validity. Each type of validity addresses different aspects of how well a test or instrument measures the intended construct.

Construct validity

Construct validity refers to the extent to which a test or instrument accurately measures the theoretical construct it is intended to measure. It involves both convergent and discriminant validity, as it assesses whether the test correlates well with other measures of the same construct (convergent validity) and does not correlate with measures of different constructs that should not be related (discriminant validity). Establishing construct validity is crucial for ensuring that the test truly reflects the underlying theoretical concept.

For example, a new intelligence test should demonstrate construct validity by correlating well with other established intelligence tests (convergent validity) and not correlating with unrelated constructs like personality traits (discriminant validity). High construct validity ensures that the test is a meaningful measure of intelligence.

Face validity

Face validity is the extent to which a test appears to measure what it claims to measure, based on subjective judgment. Unlike other forms of validity, face validity does not involve statistical analysis but rather relies on the assessment of experts or stakeholders.

Although face validity does not rely on statistical validation, it is important for ensuring that the test is acceptable to those who use or take it.

For instance, a customer satisfaction survey should have items that clearly relate to customer experiences and perceptions. If the survey items are straightforward and relevant, the survey is said to have high face validity. While not a statistically based measure, face validity helps ensure that the test is perceived as relevant and appropriate by its users.

Content validity

Content validity assesses whether a test adequately covers the entire range of the construct it aims to measure.

This type of validity involves a thorough examination of the test items to ensure they represent all aspects of the construct. Content validity is particularly important in educational and psychological testing, where comprehensive coverage of the subject matter is essential.

For example, a math proficiency test should include items that cover all relevant areas of mathematics, such as algebra, geometry, and arithmetic. High content validity ensures that the test provides a complete and accurate assessment of the construct.

Criterion validity requires demonstrating that a new measurement tool or test accurately reflects or predicts an outcome based on an established criterion. This process requires rigorous methods to ensure the new measure is both reliable and valid.

The following subsections outline the key steps in establishing criterion validity.

Selecting appropriate criteria

The first step in establishing criterion validity is to select appropriate criteria against which the new measure will be evaluated. The chosen criteria should be well-established, reliable, and relevant to the construct being measured.

For example, if a new test is designed to assess academic performance, the criterion measure could be students' grades or scores from a widely accepted standardized test. The selected criterion should accurately reflect the construct to ensure a meaningful comparison.

Criterion validity testing

Criterion validity testing involves comparing the new measure with the chosen criterion measure to evaluate their relationship. This process typically includes conducting correlational studies to determine the strength and direction of the relationship between the two measures.

A high correlation indicates that the new measure has strong criterion validity, suggesting it accurately reflects the criterion measure.

For example, to test the criterion validity of a new depression scale, researchers might administer both the new scale and an established depression inventory to the same group of participants.

By analyzing the correlation between the scores from both measures, researchers can assess the criterion validity of the new scale. Statistical techniques, such as Pearson's correlation coefficient, are commonly used to quantify the strength of the relationship.

Addressing potential challenges

Establishing criterion validity can present several challenges, such as finding suitable criterion measures and accounting for external factors that may influence the results. Researchers must carefully select criterion measures that are not only relevant but also free from biases and errors.

Additionally, external factors, such as participants' varying levels of motivation or environmental influences, can affect the accuracy of the criterion validity assessment.

To address these challenges, researchers should conduct thorough pilot testing and use multiple criterion measures when possible. Employing a range of statistical techniques can also help to control for external factors and provide a more robust evaluation of criterion validity.

Powerful qualitative data analysis starts with ATLAS.ti

Download a free trial of ATLAS.ti to see how you can make the most of your data.

Instant insights, infinite possibilities

What is criterion validity?

Last updated

7 February 2023

Reviewed by

Cathy Heath

Criterion validity or concrete validity refers to a method of testing the correlation of a variable to a concrete outcome. Higher education institutions and employers use criterion validity testing to model an applicant's potential performance. Some organizations also use it to model retention rates.

Before moving on, let's differentiate between norm-referenced tests and criterion-referenced tests. You've probably taken a few norm-referenced tests in school—the standardized tests taken in grade school and high school.

These tests measure a student's essential knowledge in core subjects, check whether they’re performing at their grade level, and measure their knowledge compared to other students.

We'll consider the difference between norm-referenced and criterion-referenced tests in detail later in this article. First, let's consider the types of criterion validity.

Make research less tedious

Dovetail streamlines research to help you uncover and share actionable insights

- Types of criterion validity

Two types of criterion validity exist:

Predictive validity: models the likelihood of an outcome

Concurrent validity: confirms whether one measure is equal or better than another accepted measure when testing the same thing at the same time

Predictive validity

A test that uses predictive validity aims to predict future performance, behavior, or outcome. Either the test administrator or the test taker can use the results to improve decision-making.

Real-world use of predictive validity tests

An employer might administer a predictive validity test to determine whether a person is likely to perform well in a specific job. To do this accurately, the employer must have a large data set of people who have already performed successfully in the job.

This example of employers administering a screening test is the most common application of predictive validity, but there are lots of other uses. For example, psychiatrists and psychologists might administer a psychological personality inventory to help diagnose a patient and gauge the possibility or probability of future behaviors.

General practice doctors (GPs) use risk factor surveys as a part of their new patient intake packets. The survey's results predict a patient's potential for developing a disease. For example, a doctor might counsel a patient who smokes two packs of cigarettes a day that their behavior increases their risk of developing lung cancer.

High school students who take the SAT are taking a predictive validity test. College students who take the GRE to gain admittance to graduate school are also taking a predictive validity test. The SAT and GRE both offer criterion validity because, over the long term, students' scores prove a valid predictor of their future academic performance as measured by their grade point average (GPA) if admitted to a college or grad school.

Concurrent validity

A test that uses concurrent validity tests the same criterion as another test. To ensure the accuracy of your test, you administer it as well as an already accepted test, which is scientifically proven to measure the same construct.

By comparing the results of both tests, you can determine whether the one you have developed accurately measures the variable you’re interested in. This type of criterion validity test is used in the fields of:

Social science

Real-world use of concurrent validity tests

If a psychologist developed a new, self-reported psychological test for measuring depression called the Winters Depression Inventory (WDI), they'd need to test its validity before using it in a clinical setting. They'd recruit non-patients to take both inventories—their new one and a commonly accepted, established one, such as the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI).

The sample group would take both inventories under controlled conditions. They would then compare the two test results for each member of the sample group. This process determines that the test they developed measures the same criterion at least as well as the accepted gold standard.

In statistical terminology, when the results of the sample population's WDI and BDI match or are close to each other, they're said to have a high positive correlation. In this scenario, the psychologist has established the concurrent validity of the two inventories.

- How to measure criterion validity

That brings us to measuring criterion validity. In our example of the psychology inventories, we discussed determining if the inventories functioned concurrently and to what extent they correlated, either positively or negatively.

To measure criterion validity, use an established metric. There are many options to choose from, including:

Pearson Correlation Coefficient

Spearman's Rank Correlations

Phi Correlations

Which correlation coefficient or method you use depends on:

Whether you're analyzing a linear or non-linear relationship

The number of variables in play

The distribution of your data

- Advantages of criterion validity

Criterion-referenced tests offer numerous advantages over norm-referenced tests when used to measure student or employee progress:

You can design the test questions to match (correlate to) specific program objectives.

Criterion validity offers a clear picture of an individual's command of specific material.

You can create and manage criterion-referenced tests locally.

The local administrator, such as a doctor or teacher, can diagnose problems using the test results and work with the individual to improve their situation.

- Disadvantages of criterion validity

Criterion-referenced tests also have some significant disadvantages:

Building these reliable and valid test instruments is expensive and time-consuming.

You can't generalize findings beyond the local application, so they don't work to measure large group performance across a broad set of locations.

The test takers could invalidate results by accessing the test questions before taking the test.

- Applications of criterion validity

To use criterion validity, you need both a predictor variable and a criterion variable. Examples of the predictor variable include the GRE or SAT. For the criterion variable, you need a known, valid measure for predicting the outcome of your interest.

In some areas of study, such as social sciences, the lack of relevant criterion variables makes it difficult to use criterion validity.

- Does a criterion validity test reflect a certain set of abilities?

No, a norm-referenced test reflects a particular set of abilities that are ranked. The standardized tests administered to US school students in grade school and high school, like SAT, LSAT, or GRE, reaffirm the level of learning as a score compared to other students in the same population. A population could be all sixth graders in a school, district, state, or nation.

A criterion-referenced test, such as a driving test, determines a person’s ability to drive a car safely and obey road rules to a set standard or criteria. It is a measurement of what they know themselves. Another example is a test at the end of a university semester, which is purely focused on how much a student knows about a certain topic. Students are not ranked—they either pass or fail.

- The lowdown

One of the four types of validity tests, criterion validity tests the correlation of a variable to a concrete outcome. If you've sat the ASVAB, SAT, or GRE, you took a norm-referenced test, which is different from a criterion validity test. Those tests indicate to an organization the likelihood of success.

When you design a survey or test instrument, you choose valid measures and appropriate correlation coefficients. You would also test your assessment before using it in a clinical setting to ensure construct validity , content validity , and reliability.

What are correlation coefficients?

A correlation coefficient is a descriptive statistic that sums up the direction of the relationship between variables and the strength of the correlation. A correlation coefficient ranges from -1 to 1.

You can have a correlation coefficient of 0, which denotes no relationship between the variables.

What is test-retest reliability?

Also called stability reliability, test-retest reliability refers to the clinical and research practice of administering a test twice, with an interval of a few weeks or several months between the first test and the second. This approach provides evidence of the reliability of the test.

The test administrator compares the two test results to determine their correlation. A correlation of 0.80 or above can be evidence of the test's reliability.

What is construct validity?

Construct validity refers to whether a test or assessment accurately examines the construct the researcher is testing. Take the example in the article of the psychologist creating the fictional WDI and testing it alongside the existing BDI. That test scenario established the construct validity of the WDI.

If a construct validity assessment has a positive result, we described the construct examined as exhibiting convergent validity. If the assessment does not accurately test the construct, we'd use the term discriminant validity to describe it.

What is content validity?

Also referred to as logical validity, content validity refers to how comprehensively a test or assessment fully evaluates a construct, topic, or behavior. Determining content validity requires an expert in the field or topic that the assessment is testing.

What is a valid measure?

In statistical analyses, not all measures provide valid insight into a data set. Your chosen measure needs to correspond to the construct that your assessment is testing.

For example, educators have administered the SAT since 1926. In over 90 years of its administration, it has proven to be an accurate predictor of whether the test taker will fare well in college. We can say that the SAT offers a valid measure of collegiate academic success.

Should you be using a customer insights hub?

Do you want to discover previous research faster?

Do you share your research findings with others?

Do you analyze research data?

Start for free today, add your research, and get to key insights faster

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 18 April 2023

Last updated: 27 February 2023

Last updated: 22 August 2024

Last updated: 5 February 2023

Last updated: 16 August 2024

Last updated: 9 March 2023

Last updated: 30 April 2024

Last updated: 12 December 2023

Last updated: 11 March 2024

Last updated: 4 July 2024

Last updated: 6 March 2024

Last updated: 5 March 2024

Last updated: 13 May 2024

Latest articles

Related topics, .css-je19u9{-webkit-align-items:flex-end;-webkit-box-align:flex-end;-ms-flex-align:flex-end;align-items:flex-end;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-flex-direction:row;-ms-flex-direction:row;flex-direction:row;-webkit-box-flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-box-pack:center;-ms-flex-pack:center;-webkit-justify-content:center;justify-content:center;row-gap:0;text-align:center;max-width:671px;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}}@media (max-width: 799px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}} decide what to .css-1kiodld{max-height:56px;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-1kiodld{display:none;}} build next, decide what to build next, log in or sign up.

Get started for free

- Skip to secondary menu

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

Statistics By Jim

Making statistics intuitive

Validity in Research and Psychology: Types & Examples

By Jim Frost 3 Comments

What is Validity in Psychology, Research, and Statistics?

Validity in research, statistics , psychology, and testing evaluates how well test scores reflect what they’re supposed to measure. Does the instrument measure what it claims to measure? Do the measurements reflect the underlying reality? Or do they quantify something else?

For example, does an intelligence test assess intelligence or another characteristic, such as education or the ability to recall facts?

Researchers need to consider whether they’re measuring what they think they’re measuring. Validity addresses the appropriateness of the data rather than whether measurements are repeatable ( reliability ). However, for a test to be valid, it must first be reliable (consistent).

Evaluating validity is crucial because it helps establish which tests to use and which to avoid. If researchers use the wrong instruments, their results can be meaningless!

Validity is usually less of a concern for tangible measurements like height and weight. You might have a cheap bathroom scale that tends to read too high or too low—but it still measures weight. For those types of measurements, you’re more interested in accuracy and precision . However, other types of measurements are not as straightforward.

Validity is often a more significant concern in psychology and the social sciences, where you measure intangible constructs such as self-esteem and positive outlook. If you’re assessing the psychological construct of conscientiousness, you need to ensure that the measurement instrument asks questions that evaluate this characteristic rather than, say, obedience.

Psychological assessments of unobservable latent constructs (e.g., intelligence, traits, abilities, proclivities, etc.) have a specific application known as test validity, which is the extent that theory and data support the interpretations of test scores. Consequently, it is a critical issue because it relates to understanding the test results.

Related post : Reliability vs Validity

Evaluating Validity

Researchers validate tests using different lines of evidence. An instrument can be strong for one type of validity but weaker for another. Consequently, it is not a black or white issue—it can have degrees.

In this vein, there are many different types of validity and ways of thinking about it. Let’s take a look at several of the more common types. Each kind is a line of evidence that can help support or refute a test’s overall validity. In this post, learn about face, content, criterion, discriminant, concurrent, predictive, and construct validity.

If you want to learn about experimental validity, read my post about internal and external validity . Those types relate to experimental design and methods.

Types of Validity

In this post, I cover the following seven types of validity:

- Face Validity : On its face, does the instrument measure the intended characteristic?

- Content Validity : Do the test items adequately evaluate the target topic?

- Criterion Validity : Do measures correlate with other measures in a pattern that fits theory?

- Discriminant Validity : Is there no correlation between measures that should not have a relationship?

- Concurrent Validity : Do simultaneous measures of the same construct correlate?

- Predictive Validity : Does the measure accurately predict outcomes?

- Construct Validity : Does the instrument measure the correct attribute?

Let’s look at these types of validity in more detail!

Face Validity

Face validity is the simplest and weakest type. Does the measurement instrument appear “on its face” to measure the intended construct? For a survey that assesses thrill-seeking behavior, you’d expect it to include questions about seeking excitement, getting bored quickly, and risky behaviors. If the survey contains these questions, then “on its face,” it seems like the instrument measures the construct that the researchers intend.

While this is a low bar, it’s an important issue to consider. Never overlook the obvious. Ensure that you understand the nature of the instrument and how it assesses a construct. Look at the questions. After all, if a test can’t clear this fundamental requirement, the other types of validity are a moot point. However, when a measure satisfies face validity, understand it is an intuition or a hunch that it feels correct. It’s not a statistical assessment. If your instrument passes this low bar, you still have more validation work ahead of you.

Content Validity

Content validity is similar to face validity—but it’s a more rigorous form. The process often involves assessing individual questions on a test and asking experts whether each item appraises the characteristics that the instrument is designed to cover. This process compares the test against the researcher’s goals and the theoretical properties of the construct. Researchers systematically determine whether each question contributes, and that no aspect is overlooked.

For example, if researchers are designing a survey to measure the attitudes and activities of thrill-seekers, they need to determine whether the questions sufficiently cover both of those aspects.

Learn more about Content Validity .

Criterion Validity

Criterion validity relates to the relationships between the variables in your dataset. If your data are valid, you’d expect to observe a particular correlation pattern between the variables. Researchers typically assess criterion validity by correlating different types of data. For whatever you’re measuring, you expect it to have particular relationships with other variables.

For example, measures of anxiety should correlate positively with the number of negative thoughts. Anxiety scores might also correlate positively with depression and eating disorders. If we see this pattern of relationships, it supports criterion validity. Our measure for anxiety correlates with other variables as expected.

This type is also known as convergent validity because scores for different measures converge or correspond as theory suggests. You should observe high correlations (either positive or negative).

Related posts : Criterion Validity: Definition, Assessing, and Examples and Interpreting Correlation Coefficients

Discriminant Validity

This type is the opposite of criterion validity. If you have valid data, you expect particular pairs of variables to correlate positively or negatively. However, for other pairs of variables, you expect no relationship.

For example, if self-esteem and locus of control are not related in reality, their measures should not correlate. You should observe a low correlation between scores.

It is also known as divergent validity because it relates to how different constructs are differentiated. Low correlations (close to zero) indicate that the values of one variable do not relate to the values of the other variables—the measures distinguish between different constructs.

Concurrent Validity

Concurrent validity evaluates the degree to which a measure of a construct correlates with other simultaneous measures of that construct. For example, if you administer two different intelligence tests to the same group, there should be a strong, positive correlation between their scores.

Learn more about Concurrent Validity: Definition, Assessing and Examples .

Predictive Validity

Predictive validity evaluates how well a construct predicts an outcome. For example, standardized tests such as the SAT and ACT are intended to predict how high school students will perform in college. If these tests have high predictive ability, test scores will have a strong, positive correlation with college achievement. Testing this type of validity requires administering the assessment and then measuring the actual outcomes.

Learn more about Predictive Validity: Definition, Assessing and Examples .

Construct Validity

A test with high construct validity correctly fits into the big picture with other constructs. Consequently, this type incorporates aspects of criterion, discriminant, concurrent, and predictive validity. A construct must correlate positively and negatively with the theoretically appropriate constructs, have no correlation with the correct constructs, correlate with other measures of the same construct, etc.

Construct validity combines the theoretical relationships between constructs with empirical relationships to see how closely they align. It evaluates the full range of characteristics for the construct you’re measuring and determines whether they all correlate correctly with other constructs, behaviors, and events.

As you can see, validity is a complex issue, particularly when you’re measuring abstract characteristics. To properly validate a test, you need to incorporate a wide range of subject-area knowledge and determine whether the measurements from your instrument fit in with the bigger picture! Researchers often use factor analysis to assess construct validity. Learn more about Factor Analysis .

For more in-depth information, read my article about Construct Validity .

Learn more about Experimental Design: Definition, Types, and Examples .

Nevo, Baruch (1985), Face Validity Revisited , Journal of Educational Measurement.

Share this:

Reader Interactions

April 21, 2022 at 12:05 am

Thank you for the examples and easy-to-understand information about the various types of statistics used in psychology. As a current Ph.D. student, I have struggled in this area and finally, understand how to research using Inter-Rater Reliability and Predictive Validity. I greatly appreciate the information you are sharing and hope you continue to share information and examples that allows anyone, regardless of degree or not, an easy way to grasp the material.

April 21, 2022 at 1:38 am

Thanks so much! I really appreciate your kind words and I’m so glad my content has been helpful. I’m going to keep sharing! 🙂

March 14, 2023 at 1:27 am

Indeed! I think I’m grasping the concept reading your contents. Thanks!

Comments and Questions Cancel reply

Criterion Validity: Definition, Types of Validity

Design of Experiments > Criterion Validity

What is Criterion Validity?

- A job applicant takes a performance test during the interview process. If this test accurately predicts how well the employee will perform on the job, the test is said to have criterion validity.

- A graduate student takes the GRE . The GRE has been shown as an effective tool (i.e. it has criterion validity) for predicting how well a student will perform in graduate studies.

The first measure (in the above examples, the job performance test and the GRE) is sometimes called the predictor variable or the estimator . The second measure is called the criterion variable as long as the measure is known to be a valid tool for predicting outcomes.

One major problem with criterion validity, especially when used in the social sciences, is that relevant criterion variables can be hard to come by.

Types of Criterion Validity

The three types are:

- Predictive Validity : if the test accurately predicts what it is supposed to predict. For example, the SAT exhibits predictive validity for performance in college. It can also refer to when scores from the predictor measure are taken first and then the criterion data is collected later.

- Concurrent Validity : when the predictor and criterion data are collected at the same time. It can also refer to when a test replaces another test (i.e. because it’s cheaper). For example, a written driver’s test replaces an in-person test with an instructor.

- Postdictive validity : if the test is a valid measure of something that happened before. For example, does a test for adult memories of childhood events work?

Beyer, W. H. CRC Standard Mathematical Tables, 31st ed. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, pp. 536 and 571, 2002. Dodge, Y. (2008). The Concise Encyclopedia of Statistics . Springer. Vogt, W.P. (2005). Dictionary of Statistics & Methodology: A Nontechnical Guide for the Social Sciences . SAGE. Wheelan, C. (2014). Naked Statistics . W. W. Norton & Company

Criterion Validity

- Reference work entry

- First Online: 01 January 2020

- Cite this reference work entry

- Kai T. Horstmann 3 ,

- Max Knaut 3 &

- Matthias Ziegler 3

91 Accesses

1 Citations

Criterion validity refers to the degree to which a test score is related to a meaningful outcome or criterion of interest.

Introduction

In its most basic form, criterion validity refers to a construct’s or test score’s relatedness to a relevant outcome of interest, the criterion. Criterion validity is conceptualized as a between-person comparison important component of the validation process of a test score. Without criterion validity, the application of a test score may not be useful.

Criterion validity can be examined with criteria assessed before ( retrospective validity ), during assessing ( concurrent validity ) or after ( predictive validity ) obtaining the test score that is to be validated. Retrospective validity would be established if the test score was related to a previously assessed characteristic of a person, such as earlier scholastic performance. While this is still a common practice, the usefulness of this approach is at least questionable. Concurrent validity...

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

AERA, APA, & NCME. (2014). Standards for educational and psychological testing . Washington, DC: AERA.

Google Scholar

Borsboom, D. (2006). The attack of the psychometricians. Psychometrika, 71 , 425–440. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11336-006-1447-6 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Borsboom, D., Mellenbergh, G. J., & van Heerden, J. (2004). The concept of validity. Psychological Review, 111 , 1061–1071. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.111.4.1061 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Brogden, H. E., & Taylor, E. K. (1950). The theory and classification of criterion bias. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 10 , 159–183. https://doi.org/10.1177/001316445001000201 .

Article Google Scholar

Ziegler, M. (2014). Stop and state your intentions! European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 30 , 239–242. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759/a000228 .

Ziegler, M., & Brunner, M. (2016). Test standards and psychometric modeling. In A. A. Lipnevich, F. Preckel, & R. Roberts (Eds.), Psychosocial skills and school systems in the 21st century (pp. 29–55). Göttingen: Springer.

Chapter Google Scholar

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Berlin, Germany

Kai T. Horstmann, Max Knaut & Matthias Ziegler

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Matthias Ziegler .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Oakland University, Rochester, MI, USA

Virgil Zeigler-Hill

Todd K. Shackelford

Section Editor information

Matthias Ziegler

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Horstmann, K.T., Knaut, M., Ziegler, M. (2020). Criterion Validity. In: Zeigler-Hill, V., Shackelford, T.K. (eds) Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-24612-3_1293

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-24612-3_1293

Published : 22 April 2020

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-319-24610-9

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-24612-3

eBook Packages : Behavioral Science and Psychology Reference Module Humanities and Social Sciences Reference Module Business, Economics and Social Sciences

Share this entry

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- The 4 Types of Validity | Types, Definitions & Examples

The 4 Types of Validity | Types, Definitions & Examples

Published on 3 May 2022 by Fiona Middleton . Revised on 10 October 2022.

In quantitative research , you have to consider the reliability and validity of your methods and measurements.

Validity tells you how accurately a method measures something. If a method measures what it claims to measure, and the results closely correspond to real-world values, then it can be considered valid. There are four main types of validity:

- Construct validity : Does the test measure the concept that it’s intended to measure?

- Content validity : Is the test fully representative of what it aims to measure?

- Face validity : Does the content of the test appear to be suitable to its aims?

- Criterion validity : Do the results accurately measure the concrete outcome they are designed to measure?

Note that this article deals with types of test validity, which determine the accuracy of the actual components of a measure. If you are doing experimental research, you also need to consider internal and external validity , which deal with the experimental design and the generalisability of results.

Table of contents

Construct validity, content validity, face validity, criterion validity.

Construct validity evaluates whether a measurement tool really represents the thing we are interested in measuring. It’s central to establishing the overall validity of a method.

What is a construct?

A construct refers to a concept or characteristic that can’t be directly observed but can be measured by observing other indicators that are associated with it.

Constructs can be characteristics of individuals, such as intelligence, obesity, job satisfaction, or depression; they can also be broader concepts applied to organisations or social groups, such as gender equality, corporate social responsibility, or freedom of speech.

What is construct validity?

Construct validity is about ensuring that the method of measurement matches the construct you want to measure. If you develop a questionnaire to diagnose depression, you need to know: does the questionnaire really measure the construct of depression? Or is it actually measuring the respondent’s mood, self-esteem, or some other construct?

To achieve construct validity, you have to ensure that your indicators and measurements are carefully developed based on relevant existing knowledge. The questionnaire must include only relevant questions that measure known indicators of depression.

The other types of validity described below can all be considered as forms of evidence for construct validity.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Content validity assesses whether a test is representative of all aspects of the construct.

To produce valid results, the content of a test, survey, or measurement method must cover all relevant parts of the subject it aims to measure. If some aspects are missing from the measurement (or if irrelevant aspects are included), the validity is threatened.

Face validity considers how suitable the content of a test seems to be on the surface. It’s similar to content validity, but face validity is a more informal and subjective assessment.

As face validity is a subjective measure, it’s often considered the weakest form of validity. However, it can be useful in the initial stages of developing a method.

Criterion validity evaluates how well a test can predict a concrete outcome, or how well the results of your test approximate the results of another test.

What is a criterion variable?

A criterion variable is an established and effective measurement that is widely considered valid, sometimes referred to as a ‘gold standard’ measurement. Criterion variables can be very difficult to find.

What is criterion validity?

To evaluate criterion validity, you calculate the correlation between the results of your measurement and the results of the criterion measurement. If there is a high correlation, this gives a good indication that your test is measuring what it intends to measure.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

Middleton, F. (2022, October 10). The 4 Types of Validity | Types, Definitions & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 16 September 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/validity-types/

Is this article helpful?

Fiona Middleton

Other students also liked, qualitative vs quantitative research | examples & methods, a quick guide to experimental design | 5 steps & examples, what is qualitative research | methods & examples.

- Privacy Policy

Home » Validity – Types, Examples and Guide

Validity – Types, Examples and Guide

Table of Contents

Validity is a fundamental concept in research, referring to the extent to which a test, measurement, or study accurately reflects or assesses the specific concept that the researcher is attempting to measure. Ensuring validity is crucial as it determines the trustworthiness and credibility of the research findings.

Research Validity

Research validity pertains to the accuracy and truthfulness of the research. It examines whether the research truly measures what it claims to measure. Without validity, research results can be misleading or erroneous, leading to incorrect conclusions and potentially flawed applications.

How to Ensure Validity in Research

Ensuring validity in research involves several strategies:

- Clear Operational Definitions : Define variables clearly and precisely.

- Use of Reliable Instruments : Employ measurement tools that have been tested for reliability.

- Pilot Testing : Conduct preliminary studies to refine the research design and instruments.

- Triangulation : Use multiple methods or sources to cross-verify results.

- Control Variables : Control extraneous variables that might influence the outcomes.

Types of Validity

Validity is categorized into several types, each addressing different aspects of measurement accuracy.

Internal Validity

Internal validity refers to the degree to which the results of a study can be attributed to the treatments or interventions rather than other factors. It is about ensuring that the study is free from confounding variables that could affect the outcome.

External Validity

External validity concerns the extent to which the research findings can be generalized to other settings, populations, or times. High external validity means the results are applicable beyond the specific context of the study.

Construct Validity

Construct validity evaluates whether a test or instrument measures the theoretical construct it is intended to measure. It involves ensuring that the test is truly assessing the concept it claims to represent.

Content Validity

Content validity examines whether a test covers the entire range of the concept being measured. It ensures that the test items represent all facets of the concept.

Criterion Validity

Criterion validity assesses how well one measure predicts an outcome based on another measure. It is divided into two types:

- Predictive Validity : How well a test predicts future performance.

- Concurrent Validity : How well a test correlates with a currently existing measure.

Face Validity

Face validity refers to the extent to which a test appears to measure what it is supposed to measure, based on superficial inspection. While it is the least scientific measure of validity, it is important for ensuring that stakeholders believe in the test’s relevance.

Importance of Validity

Validity is crucial because it directly affects the credibility of research findings. Valid results ensure that conclusions drawn from research are accurate and can be trusted. This, in turn, influences the decisions and policies based on the research.

Examples of Validity

- Internal Validity : A randomized controlled trial (RCT) where the random assignment of participants helps eliminate biases.

- External Validity : A study on educational interventions that can be applied to different schools across various regions.

- Construct Validity : A psychological test that accurately measures depression levels.

- Content Validity : An exam that covers all topics taught in a course.

- Criterion Validity : A job performance test that predicts future job success.

Where to Write About Validity in A Thesis

In a thesis, the methodology section should include discussions about validity. Here, you explain how you ensured the validity of your research instruments and design. Additionally, you may discuss validity in the results section, interpreting how the validity of your measurements affects your findings.

Applications of Validity

Validity has wide applications across various fields:

- Education : Ensuring assessments accurately measure student learning.

- Psychology : Developing tests that correctly diagnose mental health conditions.

- Market Research : Creating surveys that accurately capture consumer preferences.

Limitations of Validity

While ensuring validity is essential, it has its limitations:

- Complexity : Achieving high validity can be complex and resource-intensive.

- Context-Specific : Some validity types may not be universally applicable across all contexts.

- Subjectivity : Certain types of validity, like face validity, involve subjective judgments.

By understanding and addressing these aspects of validity, researchers can enhance the quality and impact of their studies, leading to more reliable and actionable results.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Content Validity – Measurement and Examples

Parallel Forms Reliability – Methods, Example...

Face Validity – Methods, Types, Examples

Internal Consistency Reliability – Methods...

Test-Retest Reliability – Methods, Formula and...

Construct Validity – Types, Threats and Examples

- Open access

- Published: 16 September 2024

Transcultural adaptation and validation of Persian Version of Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care (PACIC-5As) Questionnaire in Iranian older patients with type 2 diabetes

- Sahar Maroufi 1 ,

- Leila Dehghankar 2 , 3 ,

- Ahad Alizadeh 4 ,

- Mohammad Amerzadeh 5 &

- Seyedeh Ameneh Motalebi 5

BMC Health Services Research volume 24 , Article number: 1073 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

Metrics details

The Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care (PACIC-5As) questionnaire has been designed to evaluate the healthcare experiences of individuals with chronic diseases such as diabetes. Older adults are at higher risk for diabetes and its associated complications. The aim of this study was transcultural adaptation and evaluation of the validity and reliability of the PACIC-5As questionnaire in older patients with diabetes residing in Qazvin City, Iran.

In this validation study, we recruited 306 older patients with diabetes from Comprehensive Health Centers in Qazvin, Iran. The multi-stage cluster sampling technique was used to choose a representative sample. The PACIC-5As questionnaire was translated into Persian using the World Health Organization (WHO) standardized method. The validity (face, content, and construct) and reliability (Cronbach’s alpha) of the PACIC-5As were assessed. Data analysis was conducted using R software and the Lavaan package.

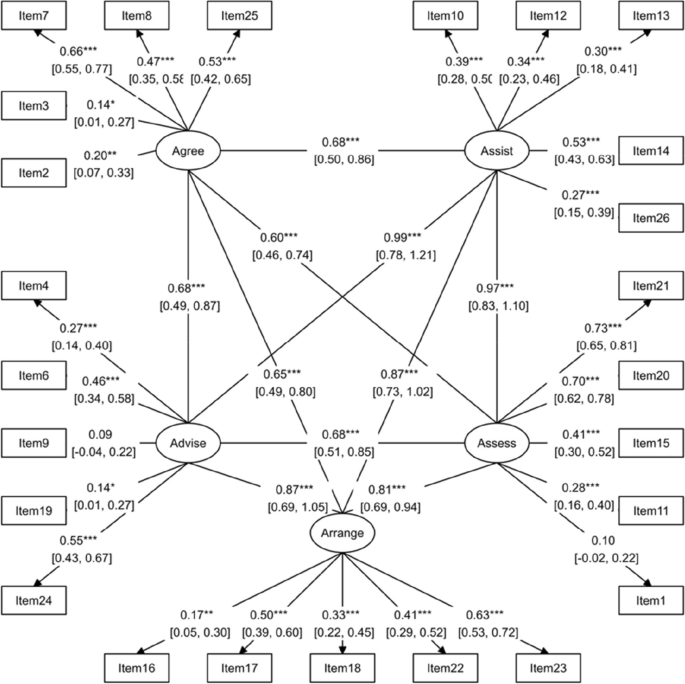

The mean age of the older patients was 69.99 ± 6.94 years old. Most older participants were female ( n = 180, 58.82%) and married ( n = 216, 70.59%). Regarding face validity, all items of PACIC-5As had impact scores greater than 1.5. In terms of content validity, all items had a content validity ratio > 0.49 and a content validity index > 0.79. The results of confirmatory factor analysis demonstrated that the model exhibited satisfactory fit across the expected five factors, including assess, advise, agree, assist, and arrange, for the 25 items of the PACIC-5As questionnaire. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the PACIC-5As questionnaire was 0.805.

This study indicates that the Persian version of the PACIC-5As questionnaire is valid and reliable for assessing healthcare experiences in older patients with diabetes. This means that the questionnaire can be effectively used in this population.

Peer Review reports

The global population is aging rapidly [ 1 ]. The fast growth of older people brings significant challenges, particularly relating to their health [ 2 ]. Approximately 75% of individuals aged 60 and above are affected by at least one chronic disease, with nearly 50% experiencing two or more chronic conditions [ 3 ]. Diabetes mellitus is among the most common and preventable chronic diseases [ 4 ]. The prevalence of diabetes is highest among older adults [ 5 ]. Nearly half of all individuals with diabetes are older adults (aged 65 years or older) [ 6 ]. The older adult population is one of the fastest-growing segments of the diabetes population. It is projected that these numbers will grow dramatically over the next few decades [ 7 ]. In Iran, Rashidi et al. (2017) found that approximately 14.4% of older adults have been diagnosed with type 2 diabetes [ 8 ].

Diabetes has emerged as one of the most serious and prevalent chronic diseases, posing a life-threatening risk, debilitating complications, substantial costs, and a reduction in life expectancy [ 9 ]. Older adults with diabetes are at serious risk of both micro and macrovascular complications [ 10 ]. Diabetes leads to an increased need for healthcare services, home care, hospitalization, and even residency in nursing homes [ 11 ]. Since self-care is a crucial aspect of diabetes management, patients need to adopt proper lifestyle habits and gain sufficient knowledge about the disease and its treatments [ 12 ].

Appropriate management of diabetes poses a significant challenge for individuals with the condition and healthcare providers [ 13 ]. Diabetes in older patients is a significant public health concern in the 21st century, and when combined with other health conditions, it can lead to exacerbated side effects [ 14 ]. Furthermore, older adults with diabetes require different types and qualities of care than other patient groups due to physiological, psychological, and social changes [ 15 ]. Iran is one of the most populous countries in the Middle East, where diabetes management is currently inadequate. Previous systematic reviews have shown that people aged over 55, especially women, tend to have poorer diabetes management [ 16 ]. A nationwide analysis of data for 30,202 patients revealed that only 13.2% of individuals with diabetes successfully attained satisfactory levels of glycemic control [ 17 ].

Managing diabetes in this group requires a comprehensive healthcare system that includes diagnosis, monitoring, and continuous medical treatment. The McColl Institute for Health Innovation developed the Chronic Care Model (CCM) to guide the delivery of healthcare services to patients with chronic conditions [ 18 ]. The CCM is a conceptual framework designed to bridge the gap between clinical research and real-life medical practice [ 19 ]. It focuses on providing proactive and planned care for chronic diseases rather than reactive and unplanned care. The CCM has six key dimensions: organization of health care, clinical information systems, delivery system design, decision support, self-management support, and community resources. It has been widely accepted for improving the care of chronically ill patients. Specifically, the “self-management support” aspect of the CCM helps patients enhance their confidence and skills to manage their illness better [ 20 ].

The Patients Assessment Chronic Illness Care (PACIC) questionnaire, developed by Glasgow et al., is used to assess patient care for chronic diseases based on the CCM [ 21 ]. It is a self-reporting instrument that provides patients’ perspectives on receiving care for chronic diseases [ 22 ]. While there are several tools to measure patients’ experiences of chronic care [ 23 ], PACIC is one of the most suitable instruments to measure the chronic care management experiences of patients as it assesses the level of alignment with the CCM [ 24 , 25 ]. The initial version of the questionnaire comprises 20 items divided into five subscales: patient activation, decision-making support, goal setting, problem-solving, and follow-up [ 26 ]. Glasgow et al. [ 24 ] expanded the PACIC questionnaire by including six additional items to assess the recommended 5As model of chronic disease care in accordance with the guidelines of the United States Preventive Services Task Force [ 27 ]. The “5As” model is an evidence-based approach to behavior change employed to improve patients’ self-management. The primary elements of this model include assessing current behavior (assess), counseling the patient (advise), reaching a shared agreement on realistic goals (agree), assisting the patient throughout the lifestyle change (assist), and providing ongoing follow-up (arrange) [ 28 ]. The PACIC-5As model has been adapted into several languages, including Hindi [ 29 ], Danish [ 30 ], French [ 31 ], Korean [ 32 ], Thai [ 33 ], Bahasa Melayu [ 34 ], Arabic [ 35 ], German [ 36 ], and Spanish [ 37 ].